870 Words

By : Lauren Peacock

Joe Donofrio, a nurse at Morristown Medical Center explains the hardest parts about being a frontline worker during the pandemic were not what the media broadcasted.

“When the director of nursing told us that nothing is an emergency anymore my heart dropped down to my stomach. It made us question what our nursing practice and guidelines were at all if you can’t even properly care for someone,” Donofrio says while trying to relax his shaking hands reaching for a glass of ice water.

“Sure, we had a shortage of equipment like PPE, toilet paper, Clorox wipes, but we also didn’t have enough life-sustaining equipment like AED’s, portable defibrillators, and Epinephrine, which is what is going to save someone’s life when they are dying.”

The pandemic opened healthcare worker’s eyes to the harsh reality of a lack of preparedness. A pandemic can happen at any moment and many felt they didn’t have enough training, supplies, and equipment necessary to safely do their jobs.

“Emergency preparedness was at an all-time minimum. Because of COVID-19, we weren’t allowed to come in close contact with patients, meaning no CPR and leaving patients to die while we stood by and did nothing,” Donofrio says while dabbing away the tears streaming down his face and reaching for his partner’s hand.

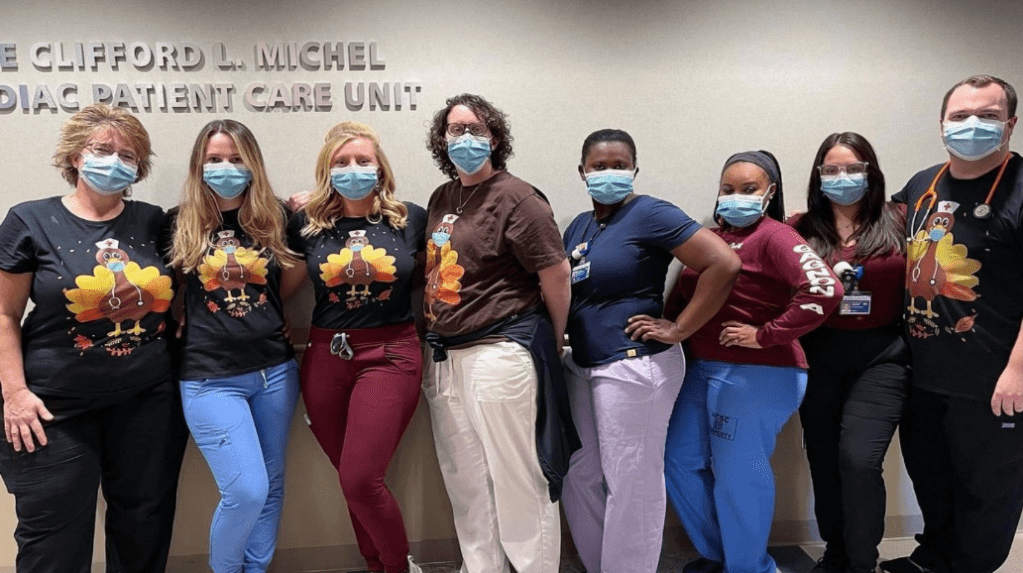

The pandemic felt never-ending, overwhelming, life-changing, etc. for everyone in any job or point in their life. Thankfully, one positive outcome is that people have found a new appreciation for health care workers and given them the spotlight, respect, and praise they deserve.

Health care workers were at the frontlines of the pandemic, not only treating those infected, but using their free and personal time to raise awareness about the facts of COVID-19, enforcing social distancing and safety protocols, fighting off conspiracy theorists and nonbelievers, and encouraging the public to get vaccinated, all while having lives of their own. Talk about a pay raise.

Joe Donofrio and co-workers become closer than ever during the pandemic. Photo Credit : Joe Donofrio

Hospital employees are taught to work at a fast time, pace and speed. New COVID-19 protocols called for slowing down and protecting yourself first.

“They didn’t want us to rush anything so we didn’t mess up any COVID-19 protocols for our safety. This goes against the morals of what nursing should be, the patient first always,” Donofrio exclaims while anxiously stroking his french bulldog.

Donofrio’s experience of being a healthcare worker during such hard times resulted in two months of mental health leave.

“All of the nurses were crying hysterically and having breakdowns. For the first six to eight months there were no psychologists deployed to COVID-19 floors. This was the first 3 years of my nursing career and I worked so hard to be prepared, but nobody could be prepared for this. “

Maya Lipshitz, a recent graduate of Tulane University and volunteer at Saint Barnabas in Livingston, NJ explains no visitors were allowed in any part of the hospital.

“All the patients were all alone, and when being treated for COVID-19 or life-saving surgery, they couldn’t have their close ones come to comfort or check in on them. A big part of recovery is knowing that you have a strong support system,” Lipshitz says while taking off her gloves, mask, and protective equipment before entering her house.

Lipshitz tried her best to take the place of family members and close friends by comforting them up to the exact moment they went into the operating rooms.

Taylor Winand, a registered nurse at Cooper University Hospital working at the Level One Trauma Center in Camden, NJ mentions how being a frontline worker during the pandemic was not only exhausting physically but mentally. It left her feeling hopeless, anxious, and burnt out.

“The unknown about what each day would hold gave me anxiety and made me take it out on my personal life. I was attacking people around me because I was so stressed about my job and it made me frustrated with some of my friend’s beliefs. I was on edge and dreading going to work,” Taylor said while watering the flowers in her garden, a new project she took on during her free time during the pandemic.

“People just think it’s 70-90 years olds with underlying conditions only at risk. I want people to know people who are healthier and younger are also dying in the hospital from COVID-19,” Winand exclaims.

Taylor Winand takes a selfie to show off her COVID-19 PPE. Photo Credit : Taylor Winand

Winand agrees with Lipshitz and mentions that another unbearable part of work was watching patients go through such hard times alone due to the no visitors policy.

“Watching people my parent’s age pass away and only talking to their family members on the phone. These are loved ones they haven’t seen in months and they can’t come to the bedside and see them before they die. It breaks your heart”

The public hysteria and politics wrapped into COVID-19 made everyone react differently and have different beliefs. Winand explains that COVID-19 is not politics or theories, it is a health risk.

“The things people have said to me are so much more frustrating because it has nothing to do with politics. We all want COVID-19 to go away but people don’t understand how horrible it is. The news isn’t even doing it justice,” Winand says while planting new vegetables in her homemade garden.